Is quantum mechanics a bit of a scam?

The fundamental proposition of physics is that there are some fundamental laws from which all else can be derived. You would therefore think that once you know the fundamental laws of quantum mechanics - the Schroedinger equation and the Born rule - you are ready to answer any question about any quantum system. But is that really the case?

The standard rulebook of physics

There has always been a bit of controversy out there about how deep the fundamental laws of physics really go - e.g. to what extent high-level phenomena such as properties of solids can be really derived from low-level laws such as the standard model.

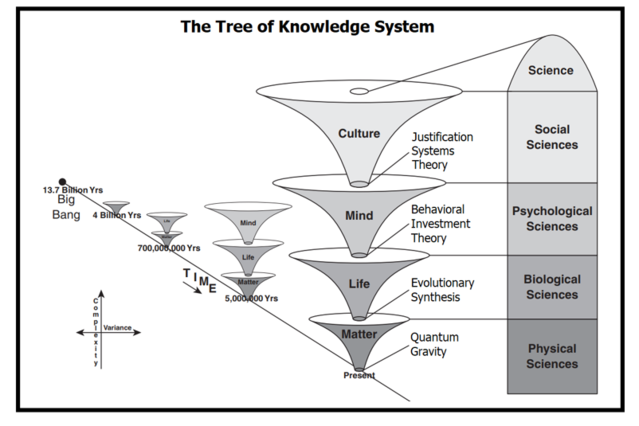

Image: One of these mind-boggling graphics discussing emergence

Still, I think it’s fair to summarise the “standard rulebook of physics” as:

- Specific problems can be generally placed in one or more specific domains: questions about charges are in the domain of electromagnetism, questions about water flow are in the domain of fluid dynamics etc.

- Every domain has its fundamental equations, and each problem can be answered by solving those equations.

Granted, this workflow may be complicated in practice, and the equations may not be straightforward to solve – but in principle, with a powerful enough computer, this is all you need.

As an example, classical mechanics (CM) typically considers the question of: given a set of massive objects with well-defined initial positions and velocities, what are their positions and velocities at some time in the future? This question can be answered by:

- Looking up the right fundamental laws (gravity, electromagnetism etc) to calculate the forces $F_i$ on the objects

- Applying Newton’s law $a_i = F_i/m_i$ to calculate the accelerations

- Integrating the accelerations of the objects to calculate future positions and velocities

In this workflow, we invoke 1) the fundamental laws of the relevant domains, 2) the fundamental laws of mechanics, and 3) the definition of position, velocity and acceleration. Sounds legit, right?

My beef with quantum mechanics

You would hope that the same workflow applies in quantum mechanics (QM). However, I have always found the standard exposition of the fundamental laws of QM contains at least one loose end that really prevents us from using them in practice. Let me walk you through an example to explain what I mean.

QM typically considers the question of: given a set of quantum objects with a well-defined initial wavefunction, what is the outcome of a set of measurements at some time in the future? This question can be answered by:

- Writing down the Hamiltonian $H$

- Integrating the Schroedinger equation $i \hbar \partial \psi / \partial t = H \psi$ to calculate the wavefunction at a given future time

- Calculating the measurement outcomes using the Born rule

In this workflow, we explicitly invoke two fundamental postulates of QM, 2) the Schroedinger equation, and 3) the Born rule 1. But what about 1)? How exactly does one decide what Hamiltonian to write down, and what fundamental laws dictate that?

The answer given to physics students is, to my taste, extremely dissatisfying. In a nutshell, it goes like this:

- Suppose your quantum objects are actually classical objects

- Look up the right fundamental laws to calculate their classical Hamiltonian $H’$, and express it terms of its “generalised position” $x$ and “generalised momentum” $p$

- Replace terms such as $x p$ and $p x$ with their symmetric version $(x p + p x)/2$

- Put a hat over $x$ and $p$ to turn them into operators

In my view, the issue with this procedure - known as “canonical quantisation” - is that while it invokes the fundamental laws of nature, it supplements them with some steps of unclear ontological status. What exactly are steps 3 - 4 doing? Is this procedure a law of nature? And if not, why exactly is it needed to calculate the outcome of quantum dynamics? I would say that canonical quantisation a loose end of QM.

To make this concrete, let’s say you want to calculate the quantum dynamics of a charged particle in a static magnetic field. Classically, we would calculate the force using the Lorentz force $F = q v \times B$. In QM, however, you’ll have to follow the procedure above to arrive at a Hamiltonian $H = (p-e A)^2/(2m)$, where $A$ is the classical vector potential of a magnetic field. Until you’ve followed the method of canonical quantization (or looked up the answer online), you’ll have no way for calculating the quantum dynamics - even though you supposedly know all the fundamental laws of quantum mechanics, as well as the rules of electromagnetism! Isn’t that crazy?

A careful reader may note: this was all about particles, but what happens when the wavefunction describes fields? Turns out there is a procedure for that too, and to arrive at the Hamiltonian of e.g. a photon you also have to:

- Take the fundamental laws of electromagnetism (Maxwell’s equation), and

- do some shady mumbo-jumbo.

That’s my gripe with QM - or at least, the QM I learned in my undergraduate.

What exactly is going on?

I think if you twist your lecturer’s arm, they are likely to tell you: “well, of course canonical quantization is not a law of nature. Is it simply a way to guess the quantum Hamiltonian from the known classical dynamics. But in reality, QM is more fundamental than CM, and so Hamiltonians are more fundamental than classical equations of motion”.

As a result, we can then say that, e.g. the fundamental law of charged particle interactions with magnetic field is really $H = (p-e A)^2/(2m)$, and that Lorentz force is basically a classical approximation of that fundamental law. In this interpretation, what the first quantization procedure provides is sort of a sanity check that the Deus Ex Machina quantum Hamiltonian is compatible with the well-known classical laws of physics.

I think this answer does make sense on paper, but it does not correspond to how people do things in practice. If you open any atomic physics textbook on a random page, it will likely say something like:

- Let’s calculate the atomic energy level shift due to the interaction between this and that quantum object

- Suppose those objects are actually little classical charged spinning balls

- If they were, the classical Hamiltonian would say …

- So let’s say the quantum Hamiltonian is the same

which is canonical quantization in disguise! What is more, we do this even when we know that the setup does not contain a good classical analogue, e.g. when Q particles with intrinsic spin.

What’s the lesson?

One of the reasons I gravitated towards physics in high school was that it was presented to me as a very “pure” science, where problems could be worked out from first principles through only self-evident procedures and thought expertiments. Only as I got further into the discipline I realised this is only about 95% true - physics is really clean, but there are loose ends nonetheless!

Now, I have it on good authority that these “loose ends” are not fundamental - they are not “bits of physics not yet understood”, but rather as “bits of physics without a simple explanation”. Usually in QM, these loose ends are pushed down to relativistic quantum field theory (“This is not quite right, but believe me, if you did the full relativistic quantum field theory calculations, all contraditions disappear”). I haven’t verified with people who know QFT how illuminated they really feel.

Still, in my view, it is helpful to follow the framing that every time you tell your student “you must trust me on this one”, you’re either talking about a fundamental law or a loose end. And just like a fundamental law in a high-level theory can actually be a derived law from a lower-level theory, hopefully a loose end in a high-level theory does not propagate down to a lower-level one.

Framed like this, I would say that undergraduate QM is, in a nutshell, composed of a few fundamental laws (including Schroedinger equation and Born rule) and one loose end (Hamiltonian quantization rules).

As always, thanks for reading, and I look forward to your comments below! In case I’m crazy and there something that everyone else gets about QM that I’ve missed, don’t hesitate to educate me. And if you’d like me to post about other loose ends in physics, let me know too!

Thanks to Shreyans Jain for comments and suggestions

-

NB some people think that the Born rule is not a fundamental law in itself, but that’s for another day. ↩