Against (most) quantum cryptography

Let me prefix by saying: quantum key distribution - or QKD - is one of the coolest ideas out there. The fact that secrecy can be certified by the laws of physics is truly crazy, and well-deserving of hype and excitement.

But what’s very secure in theory is very often laughably breakable in practice.

The popular view of QKD is the following. In general, QKD allows the distribution of shared secrets authenticated by the laws of physics, rather than by mathematical conjectures. Simple applications of QKD (think BB84) offer the highest throughput, but are subject to several loopholes. Measurement-Independent QKD (MIQKD) can be deployed to alleviate most security concerns, at the cost of a slight reduction in bit rate. For those most paranoid, Device-Independent QKD (DIQKD) is the slowest but the best answer. To put it in a different way, DIQKD is Signal, MIQKD is Whatsapp, and BB84 is Facebook Messenger.

I’ve once thought about this space like that, but I’ve since changed my mind. I’m now convinced that DIQKD is the only sensible way of building QKD systems, full stop. Non-DI QKD is just a dangerous distraction, confusing the public with its false promises and annoying the cryptographers with its glaring issues.

So what is QKD, anyway?

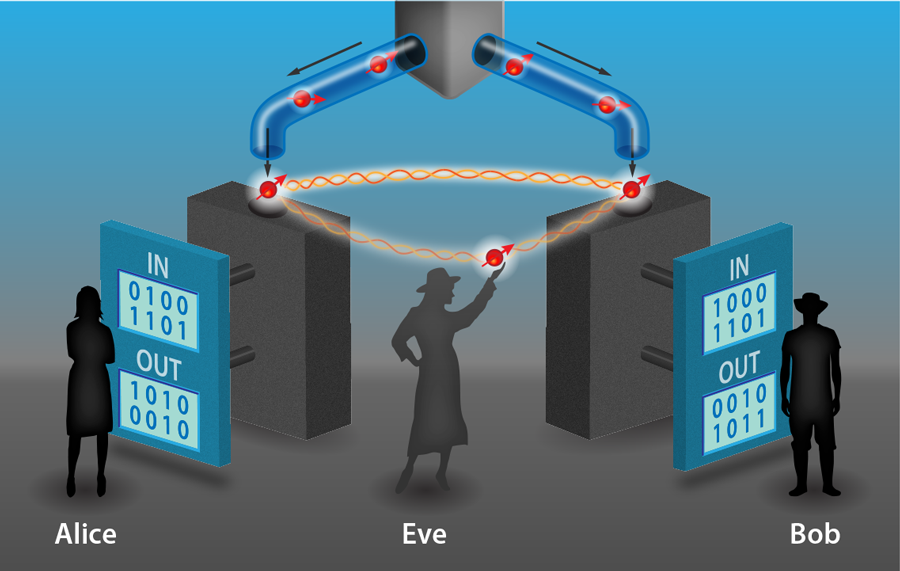

If you’ve never heard of QKD, here is a cool-looking graphic (source) that will probably not help you understand it:

A standard QKD system is composed of a few ingredients. First and foremost, it requires Alice and Bob. These guys have access to some fancy quantum equipment - usually lasers, waveplates, detectors and such - that serves to send and receive information. Then there is a protocol and a security proof. The proof will usually consider an idealised system, will be restricted to certain types of attacks, will give an idea of noise tolerance, and will be subject to several assumptions and loopholes.

Scarred by the Bell experiments, physicists hear “loopholes” and think “annoying issues that everyone knows don’t matter”, but in QKD, loopholes lead to real security threats. In cryptographic systems, assumptions must be very clearly stated and examined, or else money disappears from bank accounts.

So how do the loopholes and assumptions of idealised protocols translate into security vulnerabilities in real systems with imperfect components? Well, there is no theorem here! In other words, the security of a real-world QKD system is based on two assumptions:

- “The laws of physics”, ie. theorems about idealised equipment

- “A magic belief” that those theorems apply to the non-ideal equipment in your lab

Guess which one of these is more likely to fail us!

Quantum hacking

If this all sounds too theoretical, let’s look at some examples. Detector imperfections are the first common issue. Theoretical analysis will simply consider “single-photon detectors with finite efficiency”, and then shove all the assumptions into the “detection loophole”. But real-world photon detectors have gates, afterpulses, dark counts and quenches - and there’s no security proof that takes that all into account.

The first time I found out about how vulnerable these detectors are was from Hacking commercial quantum cryptography systems by tailored bright illumination by L. Lydarsen et al. (2011). The authors cracked commercial QKD systems as follows. Alice sends a photon to Bob following the BB84 protocol or similar. Eve intercepts the photon, and measures and re-transmits it. However, instead of sending Bob a single photon, she sends him a powerful pulse. The pulse interacts with the APD outside of the nominal detection window, making it look like a single photon when Bob’s basis aligns with Eve’s, while other basis choices look like photon loss.

This paper is just one example from a vast literature of “QKD hacks”. And every time there’s a hack, people come up with a “patch”, before the patch is hacked again and patched again. But this is a silly game! The real problem is that, as long as security is not proven for this specific detector, security remains unprovable, hence not certified by any laws of any science, only by the magic belief.

The ubiquitous nature of detector hacks prompted the development of MIQKD. In a typical scheme, Alice and Bob send laser pulses to a Bell-state measurement device, which does not need to be trusted. You may think it’s better, but while the previous scheme was breakable by shining a laser at the detector, this one can be broken by shining it at the source (it’s actually a pretty neat idea - Eve can essentially read out Alice’s waveplate settings by attempting to injection-lock Alice’s laser!).

What went wrong here? Actually, the answer seems to me fairly subtle. A common cryptographic assumption - ubiquitous to all cryptographic analysis, classical or quantum - is that Alice’s and Bob’s equipment remains “isolated” from Eve. If Eve can access Alice’s PC, there can be no secrets, as Eve can just read all of Alice’s messages off the screen. Thus, assuming isolation is obvious.

However, isolation is never perfectly true. If Alice can send signals, she can receive them too. And if the most vulnerable (i.e. quantum) equipment is directly connected to the signal output, bad things can happen. And so once again, the protocol is not fully secure.

Once again, we can play the silly game of placing isolators, monitoring the laser wavelength etc, but the underlying problems will remain. There is no security proof that applies to the exact equipment on your table, and if an analog signal can flow one way, it can flow the other way too.

Thus, the only non-silly way of doing QKD seems to require:

- Security proofs that apply to real-world equipment

- A strong ability to isolate your system from the external world.

which is DIQKD, pretty much by definition!

Device-indepedent approach

If you’re new to DIQKD, here is a nice graphic that actually illustrates the point quite well (source):

In DIQKD, Alice and Bob start every round of communication with a shared entangled state. The entanglement source need not be trusted, thus real-world sources are covered by the proof. Afterwards, Alice and Bob can disconnect any external inputs (ensuring isolation), and perform local operations using untrusted equipment. Finally, they speak to each other on a public channel, comparing measurement results. Now that is security!

It’s still unbelievable to me that DIQKD is even possible. I don’t know if it’s ever going to be useful to anyone - public-key cryptography is just so so convenient and secure - but if you want to slowly send a message that will remain secure until the end of the universe - hey, it might just be the way! But nonetheless, DIQKD is the only way to secure your messages with actual physics. Standard QKD relies mainly on wishful thinking.

DIQKD is in its infancy right now, with pretty much one experimental demonstration (?) at a speed of less than 1 bit per second. But if it eventually grows into an industrial product, it’s going to face an uphill battle - beings slower and more expensive than existing QKD, investors and funding agencies will question whether the additional security is worth the hassle. They will say things like “You physicists say DIQKD is secure, but we’ve heard you say that before about QKD, so what’s the difference?” and “QKD was supposed to be unhackable, but I’ve heard you can break it with a laser pointer, so what’s the deal?”.

Those who believe in the value of physics-based security must act preemptively to avoid this narrative taking hold.

Needless to say, none of this is to be taken as an attack on QKD researchers - it’s precisely them who did all the work testing and pointing out the limitations of these systems! DIQKD is now only a branch of QKD - and my hope is that, with time, it becomes the only branch of QKD.