How much is 100 qubits?

Writing about D-Wave, Quantum Observer notes:

I think it’s pretty obvious that, in the journey to 1 Million Qubits, 1 qubit is practically the same as 100

But is it? Not everybody agrees:

I disagree. I’d say 100 qubits is about one third of the way there.

— Joe Fitzsimons (@jfitzsimons) February 13, 2022

It’s too easy to assume all the barriers are bunched in one place, but there are barriers to each order of magnitude increase. Coupling, control, cross-talk, cooling, fridge-limit, etc.

So the question is: for what $x$ is it true that $x$ qubits are a significant milestone in the journey to 1 million? It’s a good question, and the answer does not seem simple.

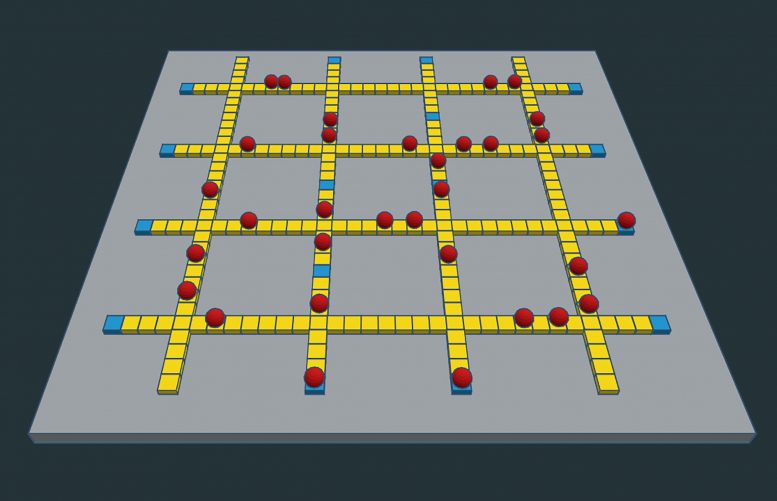

As a thought experiment, consider two (largely fictional) trapped-ion startups, Alice and Bob, both aiming at scalable fault-tolerant quantum computation. Alice’s startup plans to put 100 qubits in a linear blade trap, while Bob’s startup in interested in QCCD-type architecture.

| Alice’s plan | Bob’s plan |

|---|---|

|

|

| Image source | Image source |

Alice’s startup builds a trap in year 1. In year 2, they use a pair of powerful laser beams to perform their first two-qubit gate. In year 3, they upgrade their laser setup to an optical tweezer array, then catch and individually address 100 qubits.

Bob’s company is slower to take off. They spend several years developing a multi-layer CMOS-compatible trap fabrication process. They catch 1 ion, then 2, but then start struggling with trap charging caused by high-power laser beams. In response, they develop a laser-free gate mechanism, and perform the first gates. Later that year, as Bob’s startup catches 10 ions, they start struggling with parallel laser delivery, and learn to integrate photonic structures into their traps. Finally, Bob’s startup executes its first 100-qubit algorithm, several years after Alice.

So who is ahead? I would argue that, on the journey to 1 million qubits, Alice’s startup is really at the beginning. How might their story continue? With a 100-qubit chain, their gate errors exceed those they first measured with just a few qubits. Therefore, before attemping any quantum error correction, they will revert to using smaller chains. They briefly contemplate building larger traps with more zones, but their fancy optical tweezer system cannot support more spots without increasing aberrations. Having accepted that one trap can only support a few qubits at a time, they start working on high-cooperativity optical cavities to transfer information between traps. The resulting design is incompatible with the blade trap layout, so they rework that… and so on. Several years later, they’re still trying to control 100 qubits, just in a more scalable fashion.

In the meantime, Bob orders a few big wafers from the CMOS foundry, several dozen lasers from Toptica, puts it all together and breaks RSA. Easy peasy!

Of course, both stories are ridiculous oversimplifications that only serve to prove a point: 100 can be very close or very far from 1! Also, in reality, Alice’s startup can use the 100-qubit milestone hype to raise funding and buy out Bob… But let’s not get into that.

So how do we know if a particular 100 is a “low 100” or a “high 100”? Probably best to stop someone who just built a 100-qubit device at the next March meeting and ask them:

- What are the major roadblocks between 1 qubit and 1 million qubits for your technology? And at what qubit count do they kick in?

- How do the errors in your 100-qubit devices compare to your 10-qubit devices?

- How many cables do you need per qubit? How do you plan to control 1 million of them?

- Why don’t you build a 1000-qubit device today?